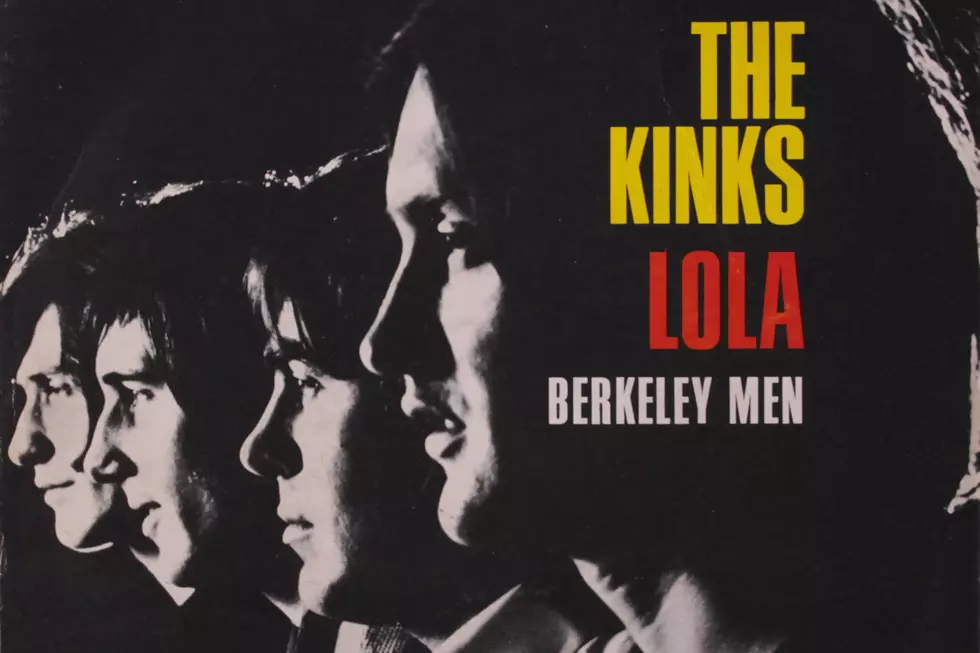

Ray and Dave Davies Recall the Kinks’ ‘Arthur’ at 50: Interview

When 1969 dawned, the once mighty Kinks were at a low ebb. Their 1968 album, The Kinks Are The Village Green Preservation Society, had been a commercial flop, bassist Pete Quaife had quit the band, they hadn’t played live in America for nearly five years – the result of a ban for “a mixture of bad management, bad luck and bad behavior,” according to frontman Ray Davies – and they were in the midst of a legal dispute that threatened no less than their collective future.

“It was a strange time,” Davies tells UCR. “But, in a way, that freed me. So I indulged myself.”

After the yearning, artistic heights of Village Green – an album that flopped upon its release but enjoyed a rebirth and reassessment in the midst of the Britpop boom of the '90s – Davies set his sights closer to home.

“Arthur was about the experience of pre- and post-War, working-class people,” says Davies of the Kinks’ next album, Arthur or the Decline and Fall of the British Empire, which has just been expanded, remixed and remastered for its 50th anniversary. “My older sister had emigrated, with our cousin Terry, and her husband, Arthur. His was the generation that had fought the war, but then spurned Churchill. I always felt he believed the work he’d been doing when they lived in London was beneath him. So he set his sights and hopes on Australia. It drew from the same well as Village Green, but that’s where the original inspiration came from."

If Village Green is elegiac and yearning, Arthur is edgy and biting. But the albums are also linked in many ways, and neatly bookend a fertile, if tumultuous period for the band, much the way Rubber Soul and Revolver do for the mid-period Beatles.

“I don’t ever confuse them, because they’re so different,” the Kinks’ guitarist, Dave Davies, says. “But there was a crossover between Village Green and Arthur and some of the characters, like we were surrounded by those same people for years.”

“I write folks songs,” Ray explains. “Strip them bare, and I’m telling the stories of the people I’ve known and the places I’ve been. But Village Green almost exists in a creative bubble. When we made the record, in early '68, I had actually given up hope of ever touring in America again, so it was almost a goodbye record, in many respects, because I didn't know if we'd make another record probably at that time. It was just a personal statement. So Arthur could have followed [Village Green’s predecessor] Something Else more naturally, I think. It's more attuned sonically to Something Else.”

Tethered to home as a result of the Kinks’ touring ban, Ray, one of rock’s premiere songwriters, looked inward, at the people and places around him in his London neighborhood for inspiration.

“I did immerse myself more in English subject matter,” Ray contends. “If we'd been on tour in America, I probably would have written about other subjects, but the records would have sounded a lot different. The band may have gone down a slightly different route.”

Still, like Village Green, Arthur is a concept album of sorts.

“Arthur was a bigger project,” Ray recalls. “I think we wanted to explore making something that was a whole album experience, rather than picking out four or five key tracks. Why make an album if it's only going to be three or four hits? I wanted to make something that would be a complete experience. Again, culture was evolving at that time. In America, bands were listening to our first records, and then exploring the long form process. The Doors had L.A. Woman. Other people were heading in that direction.”

Dave, who worked closely with his brother on the earliest incarnations of the songs that make up Arthur, also believes the songs on the album use the simple stories of his family members to help chronicle an England that may have been swinging in the late '60s, but was really crumbling all around.

“There was a lot of feeling of resentment and cynicism in the music, and definitely in Ray’s writing, because of that wrenching Rosie and Arthur thing,” Dave says, recalling, like his brother, that their sister and her husband were the original inspiration for the album. “But also it relates very well to what was happening to our generation. Growing up in the '50s, after the Second World War, as kids we were subjected to all the war stories and all the weird stuff that went on. So it’s not surprising that these things would influence Ray, listening to stories and things about the war and the characters that died, mixed up with our unhappiness, about Rosie and Arthur leaving. So the two scenarios are linked. Hence, Arthur or the Decline and Fall of the British Empire, which is its full title, actually. Because it was more like a fallen British Empire, because everybody in our sister’s generation, and Arthur’s generation, they’d fought the war, and were expecting a brand-new world. And did it ever come? I don’t think so.”

Watch a Video About the 50th-Anniversary Edition of the Kinks' 'Arthur'

And so Arthur includes the razor sharp set pieces “Victoria” and “Shangri-La,” as well as “Some Mother’s Son,” an unflinching, anti-war song, about a young soldier killed in battle, and his bereaved parents, who keep a framed picture of him with flowers on their wall.

“It’s a really powerful song,” Dave says emphatically. “It’s definitely one of the most potent anti-war songs, I think.”

“I've never directly written about politics,” Ray counters. “It's only come through in the subtext, the sound and the sonics. I throw key words in there. Rather than saying that the political situation in the world is awful, I'll throw in key words. It'll be impressionistic rather than a statement of facts. It's like that old saying, ‘If you want to send a message, use Western Union.’”

Of course, Arthur isn’t just full of biting social commentary. It also includes plaintive songs recalling good times, as well as love and loss.

“The songs are very lyrical, very English folk/country,” says Ray. “I think that what training I had was from writing and being an artist in college. I'd draw my experience from characters and things. Every tune had a different cast and subject matter. In other words, the subject matter dictated what the record would be like. The songs were character-driven. They had observations about people. It was like musical theater. And I think in our own way, we were savvy enough to know that the subject matter made the content.”

“Drivin’” and “Young and Innocent Days,” about the Davies brothers’ childhood, offer levity, and some breathing room, but still pushed the boundaries of what pop songs had offered listeners up to that point.

“’Young and Innocent Days,’ I love that song,” Dave says. “It's one of my favorites. I do it in my shows still today. That's [a great example of] the poignant pathos the Kinks were so good at.”

Listen to the 2019 Mix of the Kinks' 'Australia'

Dave has more favorites on an album he still ranks as one of his band’s best.

“It has ‘Princess Marina,’ which was quite funny, but it was unforgiving too,” he says. “But Arthur is one of my favorite Kinks albums, probably because of that intensity. It's based on real-life people like my mother's brother, and other family members, who had gone through these experiences. It's like a hangover from the Second World War. Those stories that our uncles and mother and father would have talked about, about people who died and got lost in the war, and these terrible experiences they went through.”

Ray sees Arthur in starker relief.

“As my career evolved, people expected the most intricate lyrical and rhythmically brilliant things,” Ray says. “I just wanted to write simple songs that moved people.”

Still, even if Ray’s songs were striving for simplicity, the recordings the band laid down weren’t the radio-friendly pop songs they’d become so famous for. For his part, Dave saw Arthur as a chance for the Kinks to stretch out creatively.

“I thought it was an opportunity for us all to expand, and express ourselves more as musicians, more than even on Village Green, and before that, of course, because we were recording singles that were two and a half minutes long,” he says.

“So it was a time of exploration for us, musically, and I loved it,” Dave adds. “I really got off on a lot of the playing and the jams on the record. I think it’s very empowering, a lot of the music that I'm playing on the record.”

It was also a new band, with bassist John Dalton – known as Nobby – replacing original member Quaife on the eve of the making of the album.

“It was a different band,” Dave recalls. “Fortunately, John brought his own energy to the project. When Pete left, the Kinks kind of ended in one sense. So we were starting all over again. I thought Nobby did a brilliant job in filling Pete’s shoes. They were very, very different types of musicians, but it was still a very expansive and exciting time.”

“Sometimes you can get lost in your intellect,” Ray says, doffing his producer's hat for a minute to discuss the irreplaceable chemistry the Kinks added to his songs. “You need to let the machine do its job. You need to let things inspire you. At the end of the day, it's a mechanical process getting worked out. It's important to interact.”

And if Village Green was lo-fi – “Like an indie record as opposed to an indie movie, or a record that's been shot on a handheld camera,” says Ray – Arthur benefited from the Kinks being given the opportunity to record in their label’s larger facility, Pye Records’ Studio One.

“The record company gave us more room -- literally -- in that the studio that time was bigger and had an 8-track Scully tape machine, which was state-of-the-art in those days,” recalls Dave. “With that big recording head on the analog tape, there was a much better bass response. So we were very lucky to have the time to record what we wanted, and how we wanted to record it, but also to be able to get it to sound great.”

Listen to the 2019 Mix of the Kinks' 'Shangri-La'

If the newly remastered Arthur sounds better than ever, it also feels particularly prescient in this Brexit age.

“Particularly in England, there is no working-class culture,” Ray says, reflecting on his home country both at the time of Arthur and now. “You have the underclass and the upper class. You have the rich and you have the people with nothing in Britain.”

“We’re still in this state of confusion,” Dave says wryly, referencing the Kinks' 1983 hit album of the same name. “There are so many unresolved things going on in the world, but especially in England, what with Brexit and everything else. It’s opened up the old wounds and resentments – the questions of 'Where are we going?' that Arthur dealt with 50 years ago – and all that stuff is still relevant today.”

Kinks Albums Ranked

More From Eagle 106.3