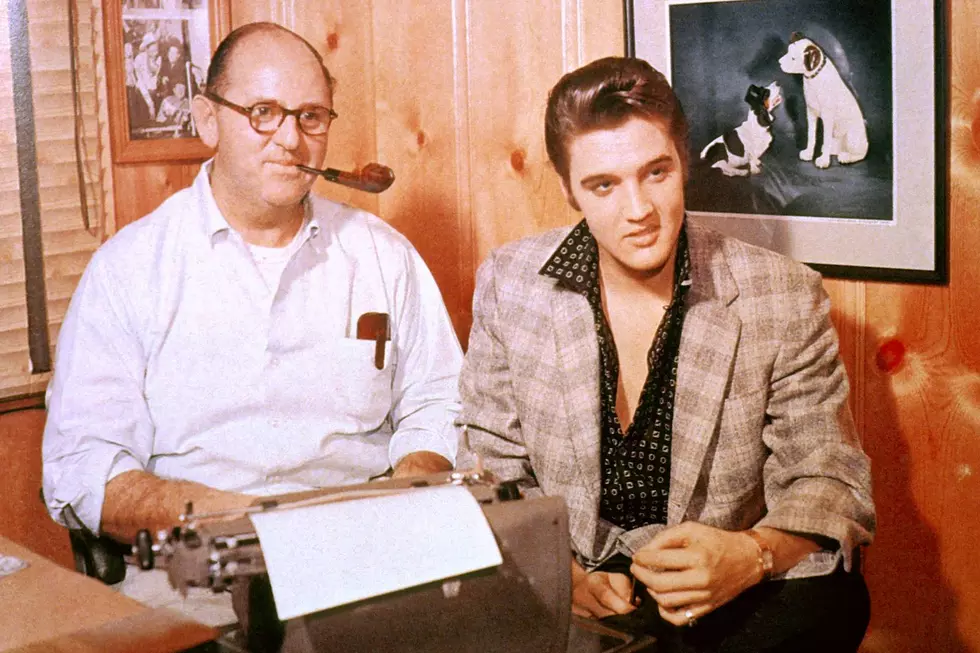

Was Colonel Tom Parker the Villain ‘Elvis’ Makes Him Out to Be?

Few figures in rock history are as controversial as Colonel Tom Parker.

The Dutch-born carny-turned-manager plucked Elvis Presley from obscurity and turned him into one of the biggest stars in history. But the two had an often-thorny relationship, and Parker's business practices have been widely scrutinized and criticized over the years. He has been frequently accused of halting Presley's career by refusing to let him tour overseas, relegating him to B-movie purgatory for much of the '60s and sucking him dry as a Vegas lounge act rather than letting him flourish artistically.

In Baz Luhrmann's new Elvis biopic, out Friday, Tom Hanks portrays Parker as this kind of Machiavellian supervillain. And while Hanks' bombastic performance is almost hilarious in its absurdity, his actions and motivations throughout the movie are fairly rooted in reality, according to biographers and former members of Parker and Presley's entourage.

Born Andreas Cornelis van Kuijk in Breda, Netherlands, in 1909, Parker illegally emigrated to the United States at age 20, whereupon he changed his name and assumed a new identity. (A popular but completely unsubstantiated theory suggests Parker fled Breda after killing the wife of a greengrocer.) He got his start as a carnival worker before entering the music business, taking on clients such as the crooner Gene Austin and country singers Eddy Arnold, Hank Snow and Tommy Sands. Parker also assisted Louisiana governor Jimmie Davis on his campaign, and for his efforts he received the honorary title of "Colonel."

Parker met Presley in 1955 and soon convinced RCA Victor to buy the singer out of his contract with Sun Records. In 1956 Presley signed a contact that made Parker his sole representative. Together, their success was meteoric, as Presley's debut single for RCA Victor, "Heartbreak Hotel," became a No. 1 hit and turned him into a superstar. It was the beginning of a staggering run of chart-toppers that would last into the early '60s.

Listen to Elvis Presley's 'Heartbreak Hotel'

Presley's fame came at a price, though, with Parker taking up to 50% of the singer's earnings, whereas most managers took 10 to 15%. Parker argued that Presley was his sole client and thus the commission was well-earned. But money wasn't the only point of contention in Presley and Parker's partnership. After returning from a two-year military stint in 1960, Presley began starring in a slew of Hollywood films that were successful at the box office but almost universally panned by critics. Parker didn't care; he saw that he could extract maximum profits out of Presley by keeping him on a rigorous film schedule and using the accompanying soundtracks to fulfill his contractual obligations to RCA.

It's up for debate whether Parker killed Presley's music career in the early '60s; it's fully possible that his career would have languished anyway among the new wave of shaggy-haired, countercultural rockers who wrote their own music, such as the Beatles and Rolling Stones. Nevertheless, Presley's dreams of being a serious actor went unfulfilled, and he was stuck recording subpar musical material for much of the '60s.

By 1968, Presley's musical career was in dire straits, but he reversed his fortunes with an eponymous comeback special, a televised performance that aired on Dec. 3, 1968, and found him playing in front of his first live audience in seven years. It was a smashing success that saw Presley in tip-top form, and offers quickly rolled in from around the world for him to perform. Parker, however, wouldn't let his client overseas. As an undocumented immigrant, Parker didn't have a passport and feared that if he ran into trouble abroad, he wouldn't be able to return to the States. He also wouldn't let Presley make the trek with anyone else because he wanted to have complete control over his "attraction" — to borrow Parker's old carnival vernacular — at all times.

Watch Elvis Presley Perform 'Trying to Get to You' on the '68 Comeback Special

Instead, Parker found a lucrative stateside option for his cash cow. In 1969, Presley went to Las Vegas to begin performing at the newly opened International Hotel, which became known as the Las Vegas Hilton in 1971. Between 1969 and his death on Aug. 16, 1977, Presley played over 600 shows at the Hilton. The singer was raking in cash hand over fist from these engagements, but he found them artistically stultifying and grew to resent Las Vegas.

Parker kept Presley performing nonstop in Vegas to pay off his gambling debts, which ballooned to $30 million at the Hilton alone by 1977. "It was common knowledge that Parker was deeply into the 'people' in Vegas because of his enormous gambling losses," Presley's personal hairstylist Larry Geller said in Alanna Nash's book The Colonel: The Extraordinary Story of Colonel Tom Parker and Elvis Presley. "Elvis became more aware of this as time went by and knew that he was Colonel Parker's bait and ransom, that Parker owned him, and whatever losses Parker incurred, Elvis would ultimately pay off by performing."

Meanwhile, the Colonel would also book Presley in Podunk towns, put him up in dumpy hotels and have him play miserable venues like high school gymnasiums. He argued that fans who lived off the beaten path deserved to see the King as well. In reality, he was leaning on his old carny connections to pull favors and trying to cut costs between bigger cities and venues.

As Parker continued to work Presley ragged, the singer's health deteriorated as he became dependent on prescription drugs to keep him going onstage and put him to sleep at night. But in 1973, the Colonel committed the ultimate betrayal, selling Presley's entire back catalog to RCA for $5.4 million, a gross undervaluation for one of the most substantial catalogs in music history. After taxes, Presley only saw about $2 million of it, much of which went toward his divorce settlement with his ex-wife Priscilla.

Watch Elvis Presley Perform 'Jailhouse Rock' Live in 1977

Parker's deal meant that Presley's estate would receive no royalties on any of his songs recorded prior to 1973. Following Presley's death, Elvis Presley Enterprises sued Parker for mismanagement, using this deal as evidence. The case was settled out of court in 1983, and in exchange for $2 million, Parker had to relinquish all video and audio recordings of Presley and give up his earnings on all Presley-related materials for the next five years.

The sale of his catalog was the final nail in the coffin of Presley and Parker's relationship. From 1973 to his death, the rocker had little direct contact with his manager and lived out the rest of his days as a depressed, drug-addicted shell of his former self. Parker also torpedoed Presley's last shot at serious movie stardom after he was approached to star alongside Barbra Streisand in the 1976 remake of A Star Is Born. Warner Bros. and Streisand's First Artists production company offered Presley $500,000 plus 10% of the net profits for the role, to which Parker responded with a demand for $1 million and 50% of gross profits, $100,000 in expenses, approval on all of Presley's songs and a piece of the soundtrack. Parker never heard back from First Artists, and the role instead went to country singer Kris Kristofferson.

Despite Presley's obviously poor condition, he retained a grueling performance schedule in Vegas and on the road. Parker certainly wasn't ignorant to Presley's health woes. As late as May 1977, he saw the singer barely conscious backstage before a gig in Louisville, Ky. According to Geller, Parker saw Presley's doctor administering him drugs and dunking his head in ice water in order to get him ready to perform. But the Colonel had no interest in the King's health. "You listen to me!" Parker reportedly shouted. "The only thing that's important is that he's on that stage tonight! Nothing else matters!"

Three months later, Presley was dead.